A homily for a weekday in Holy Week

Two years ago, I had the honor and privilege of preaching at an interfaith Holy Week service, reflecting on what Jesus did, how he got there, and how our lives affected his. I offer it to you again.

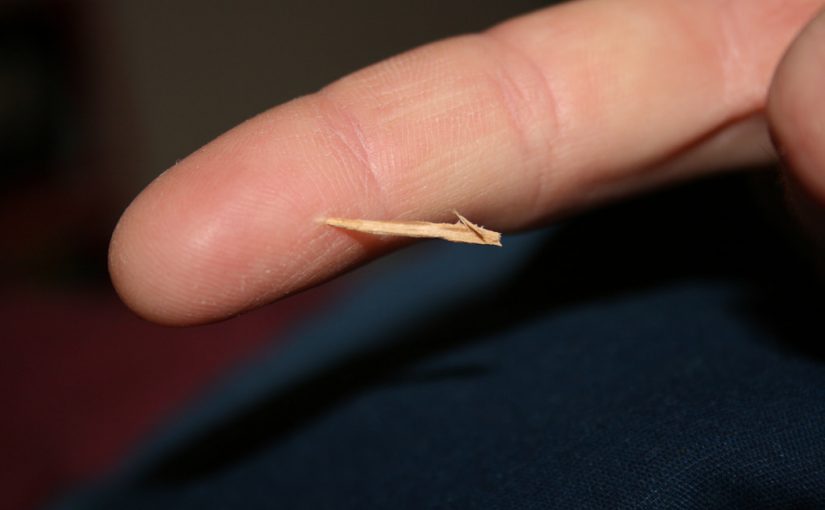

Have you ever gotten a splinter?

A little shard of wood in your fingertip or palm?

Maybe in that spot between the first and second joints on your pointer?

The splinter might have been pretty long, or didn’t go in that far, and you could pull it out quickly, in one piece.

It might have buried itself deep, or the end snapped off, and you had to find some tweezers or stick the end of a pin in a match flame to dig it out.

Perhaps you didn’t get it out right away, and it got irritated, infected, red and sore and maybe really gross. You could get blood poisoning, and at this point you’d need a doctor.

For a splinter. This long. Weighing so little that only a scientific scale can measure it.

A splinter.

Jesus of Nazareth got splinters. As a contractor, as a carpenter in the first century, he worked with simple tools, rudimentary tools. Hand saws, hand planes, mallets, wedges. Nothing stamped “Craftsman” on the side, even though stories about him say he indeed was a craftsman.

His supplies came from around him – trees he or someone cut down, rocks chiseled and split, mud and mortar hand-mixed. Carried on his back, hauled in a barrow, dragged at the end of a rope. No Home Depot cart; no Lumber Liquidators delivery truck. Just the strength of a hard-working man.

Jesus got splinters.

And God though he was, it’s painfully likely that he mis-hit a nail and smashed his thumb with a hammer once or twice. Rocks and bricks gave him blisters and calluses and absolutely scraped his knuckles.

Jesus worked with simple tools and rough materials: Aleppo pine, Hawthorn, Sycamore, Laurel, Willow, cut not at a sawmill nor sanded smooth. The carpenter had his work cut out for him.

Jesus worked with simple tools and rough materials: tax collectors and prostitutes and fishermen. Andrew, James and John. Simon Peter. None of them sanded smooth. The rabbi had his work cut out for him. He preached in parables to keep his message understandable, relatable. He preached a new covenant of divine peace and a baptism of water and the spirit.

Jesus still works with rough materials: us.

Men and women who sin, who turn their backs on our loving God and Creator, who refuse to see Christ in all of Creation, and especially not in their sisters and brothers. Sinners who see differences as the key to labeling and sorting and, once everyone has had some sort of triangle stapled onto them, the most efficient way of pushing people to the margins. Once these undesirables are at arm’s length, it’s easy for those who turn their back on God to build walls to keep them out.

Jesus still works with simple tools. No implement of his is simpler or more elegant than the Law of Love.

Love God, the source of love, and thereby live in love.

Love your neighbor as yourself, for the love of God.

Jesus wrote this law not in ink, but in blood, his blood. Shed for us, for our salvation, on a cross of wood at a filthy place named for rotted corpses. A cross of wood exactly like the wood he had cut and trimmed and smoothed from his boyhood. Exactly like the wood that undoubtedly gave him splinters.

Just for a moment, let’s compare splinters to sin.

If you track sins in bookkeeper-fashion, if you count each stolen candy bar or bigger-than-a-little-white lie – or far worse transgression – as a sin, as a mark against you in the Book of Life, then any one of us could have contributed mightily to the wood of the cross, one splinter at a time.

But if you view sin holistically, if you consider sin to be a life lived in the darkness, committed by a person rejecting the Light of Christ, then you can see how all those splinters combined – millions and billions of them squeezed together like modern plywood – all those splinters gave the Sanhedrin and the Romans plenty of wood to hang Jesus on.

The sins of everyone who ever lived or ever would live.

History is hazy on how much of the cross the Christ drag-carried to Golgotha. A typical prisoner of the Romans who had been condemned carried the crosspiece, something like the landscaping ties we use in our gardens today. Estimated weight: 75 to 125 pounds.

The Nazarean was no ordinary prisoner, though, and to make a horrible example of him, the Romans may have forced him to carry the upright and the crosspiece, some 300 pounds of wood. No wonder the Cyrenean was pressed into service to assist Jesus. Despite his years of work, and the rugged body that came with it, the scourged 33-year-old with blood flowing from razor-sharp thorns mashed into his head had to struggle up Mount Calvary.

In Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” the ghost of Jacob Marley tells Scrooge about his fetters: “I wear the chain I forged in life. I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.” Marley speaks of the sins he and Scrooge committed by choosing to steal, to extort. For him, for them, the sins accumulated as chain links.

Jesus was nailed to the cross all of humanity created. We made it splinter by splinter, and yard by yard.

We’re still adding to it.

Jesus accepted the will of the Father; he felt the pain, the agonizing, physical pain that mirrored the emotional pain our loving God feels when we walk in darkness, when we break our family ties with God.

And on our behalf, as a true representative of all humanity, Jesus conquered the cross. He conquered sin. Every sin. Millions and billions.

His resurrection from the dead gave us the new birth that we all need, that we all should choose.

In coming down from the cross and rising from the dead, Jesus shattered all misconceptions about how people are to treat each other on this earth, and how we are to daily renew and strengthen our relationship with God. To embrace the Law of Love.

We do this by avoiding the big sins that masquerade as tiny splinters, and by plucking out the ones we cannot avoid. We pray for forgiveness and healing and the grace of God to stay away from repeat injury.

We do this by never becoming splinters in the lives of our sisters and brothers whoever and wherever they may be, and by never being polluting splinters that diminish the glory of God’s creation.

We do this by remembering how the wood of the cross came to be, and by remembering how painful even the tiniest splinter can be.

To ourselves.

To God.

“Hagar the Horrible,” the comic strip by Dik and Chris Browne in which the eponymous character’s job is pillaging and stealing, takes a backhanded swipe at this notion. Hagar’s motto?

“Hagar the Horrible,” the comic strip by Dik and Chris Browne in which the eponymous character’s job is pillaging and stealing, takes a backhanded swipe at this notion. Hagar’s motto?

Well, maybe “community” is stretching it. At 2 a.m., the Pathmark had an assortment of fellow travelers who only slightly acknowledged each other’s presence as they scooped up everything from the cliché bread and milk to a full week’s — or full fortnight’s — load of groceries.

Well, maybe “community” is stretching it. At 2 a.m., the Pathmark had an assortment of fellow travelers who only slightly acknowledged each other’s presence as they scooped up everything from the cliché bread and milk to a full week’s — or full fortnight’s — load of groceries. I think again of the night crew at the late, lamented Pathmark.

I think again of the night crew at the late, lamented Pathmark.

Let’s start with the commercial for Jardiance that features a band director just a little too into marching onto the field with her high schoolers. Hips sway, arms swing, she’s totally in control. We’re to believe her Type 2 diabetes is under control as well.

Let’s start with the commercial for Jardiance that features a band director just a little too into marching onto the field with her high schoolers. Hips sway, arms swing, she’s totally in control. We’re to believe her Type 2 diabetes is under control as well.  Next is the “aww-ahh-ee-ahh” band for Humira, whose singer battles a serious intestinal disorder. It seems an odd career choice for someone whose condition is not yet being treated.

Next is the “aww-ahh-ee-ahh” band for Humira, whose singer battles a serious intestinal disorder. It seems an odd career choice for someone whose condition is not yet being treated.

It went kerblooey.

It went kerblooey.